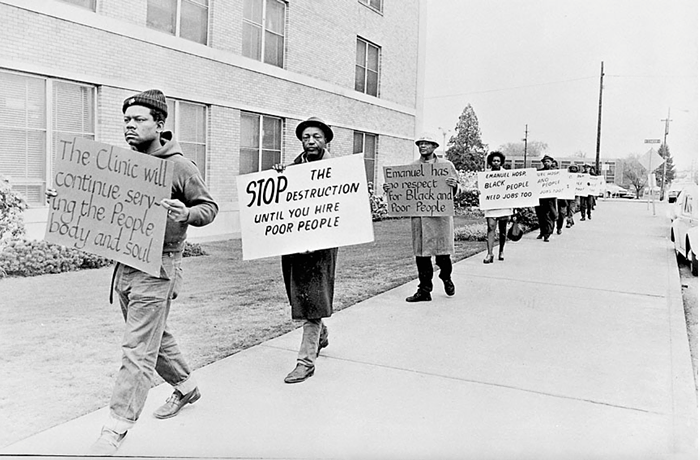

A new Portland State University (PSU) report has underscored a long-simmering request from Portland’s Black community: Pay reparations to the families forcibly displaced from the Albina neighborhood with the expansion of Portland's Emanuel Hospital in the 1970s.

The report, authored by a group of PSU urban planning graduate students, documents the history of the inner Northeast Portland neighborhood and the financial and emotional harm done to the Black community that used to call it home. It was produced in partnership with Emanuel Displaced Persons Association 2 (EDPA2), a community group made up of descendants of the Black families displaced from the neighborhood.

"This study gives significance to our battle," said Byrd, a co-founder of EDPA2 who goes by her first name. "It helps connect the pieces."

Byrd's family home was one of the 300 residences and businesses owned by Black Portlanders in the Albina neighborhood that were razed in 1971, after the city declared the area to be "blighted." Using the power of eminent domain, the city then transferred 55 acres of mostly private property to Emanuel Hospital (now Legacy Emanuel Medical Center) in the name of "urban renewal."

At the time, the city agreed to create "low to moderate" income housing for each family displaced by the hospital expansion. While the city contends that it's created some 2,000 affordable housing units in North and Northeast Portland over the past several decades, EDPA2 contends that those homes were never made available to displaced families. And, in the cases that they were, the group argues that replacing an owned house with a rented apartment does little to restore the generational wealth and stability achieved through the displaced Portlanders' prior home ownership.

The PSU report helps quantify that loss. Calculating in the skyrocketing property values that accompanied the gentrification of the Albina neighborhood alongside price inflation, the report estimate that displaced Albina families are owed at least $89 million in property wealth appreciation.

"Population growth and massive public investment have resulted in enormous gains in value that the public—and specifically the community that was forcefully removed—was not able to benefit from," the report reads.

The researchers recommend the city—as well as Legacy Emanuel—consider repaying those funds to descendants through direct payments not unlike the funds individuals received through the CARES Act. If this is too much of a financial burden on government coffers, the report suggests city officials "fill in the gaps through advocacy and support for higher levels of government involvement at the state and federal level" to support the displaced community.

The report also recommends granting the descendants of displaced Portlanders access to property ownership, whether that's by waiving housing permit fees or offering grant funding. Researchers say this is akin to Marion County waiving building permit fees for families who lost their homes in the Beachie Creek Fire.

Researchers urge the city to create a restitution task force made up of those whose families were impacted by the urban renewal work in Albina to inform a formal repayment plan.

"The hard work—the critical work—is not in saying we won’t do it again, it is in looking earnestly into the eyes of those harmed, acknowledging, apologizing, and doing what it takes to make it right," the report reads.

This idea was first raised before City Council in late 2020, when commissioners were set to vote on a plan to request $67 million in federal funding to build more affordable housing in Northeast Portland. At the time, city officials noted that the federal funds couldn't legally be used for restitution payments, something that City Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty had inquired about. Hardesty noted that City Council needs to have "a conversation about reparations."

According to the report, researchers attempted to speak with commissioners Mingus Mapps and Carmen Rubio for the report, as both had also shown interest in restitution. Researchers said neither were able to meet with them.

Byrd said she's hopeful that this report will galvanize public support and spark change within City Hall. She also considers it a critical resource for anyone seeking clarity on the history of Portland's Black community.

"It's a sweet relief for me to have this out there," said Byrd. "I hope that means it will attract the attention of more people."

EDPA2 will host a virtual discussion about the report's findings on February 14 at 6 pm.