State health officials are optimistic that a recent decrease in respiratory cases and hospitalizations will continue throughout the spring and could allow the state to remove its masking requirement in healthcare settings.

Dean Sidelinger, state epidemiologist for the Oregon Health Authority (OHA), said at a press briefing Thursday that the state is seeing “incredibly good” trends in its respiratory illness numbers even as he cautioned that state hospital capacity remains stretched.

“Overall, hospital admissions for respiratory illnesses have declined dramatically since early December,” Sidelinger said. “However, hospitals remain at or near capacity as large numbers of people continue seeking care for all types of medical conditions.”

Oregon still has a state declaration of emergency in place to make it easier for retired and out-of-state practitioners to provide care in the state’s hospitals, but the worst of the winter surge of illnesses appears to be over.

That news is particularly welcome after Oregon hospitals, like many around the country, were overwhelmed by a wave of COVID-19, flu, and RSV cases last year. In Portland, a number of major hospitals enacted crisis standards of care for the first time since the COVID pandemic began.

Sidelinger said that as the public health situation changes, OHA is “reexamining all pandemic-era policies in place.”

“We recognize that we are entering yet another important, more sustainable phase of the pandemic,” Sidelinger said. “Even as we monitor for temporary increases in COVID-19 and Influenza B activity in the community, hospitalizations are expected to continue trending downwards.”

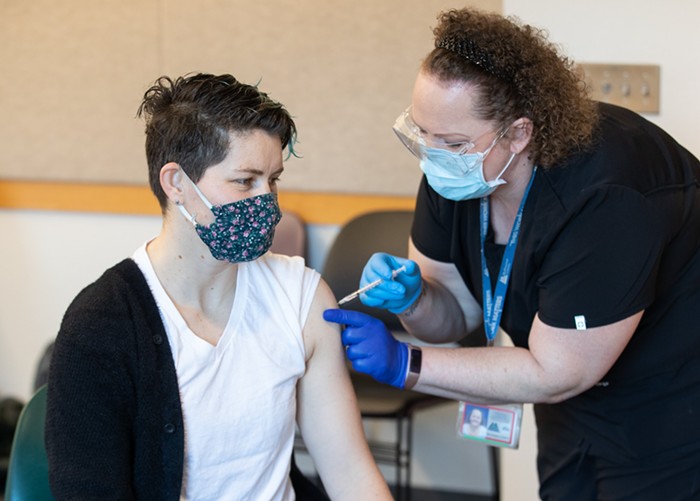

Sidelinger said that, should the current trends continue, the state should be able to lift its masking requirement in healthcare settings—one of the last remaining public health measures left in place from the first months of the pandemic.

According to Sidelinger, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) expects the rate of COVID hospitalization to remain flat in February. Changes in the federal government’s handling of the virus may also factor into Oregon’s COVID outlook.

Last month, the White House announced that it will allow the COVID public health emergency first enacted in January 2020 to expire in May—a decision that will open the door for pharmaceutical companies to start charging for vaccines, tests, and treatment. The handling of the latter stage of the pandemic has been a major political issue in Washington DC, where House Republicans voted to pass a bill immediately ending the public health emergency just days after the Biden administration’s announcement that it would end in May.

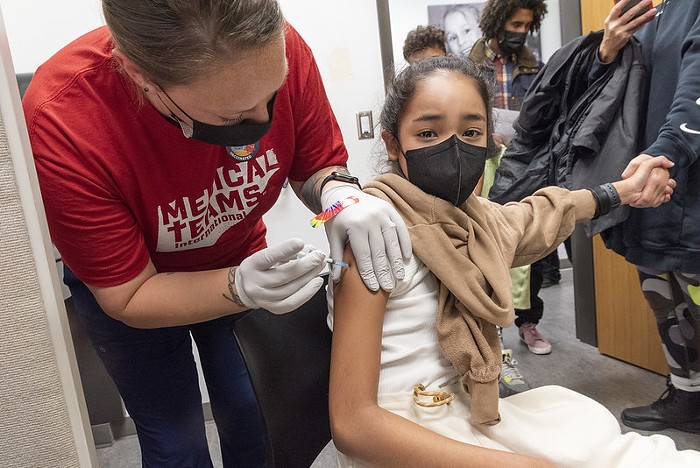

The end of the public health emergency has prompted concerns that corporations will begin charging exorbitant prices for vaccines, with the Kaiser Family Foundation estimating that the price of vaccines may average between $96 to $115 per dose—a major issue for people who are uninsured or underinsured. Sidelinger said the OHA is concerned that the cost of commercialization could dissuade people from getting vaccinated against COVID-19 or getting treatment, but that it is not a major concern yet.

“Things are not going to change soon and are not going to change overnight in terms of access [to the vaccine],” he said. “The federal government has purchased a large number of vaccines and therapeutics that are available to individuals free of charge, and that won’t change in the short-term.”

More than 86 percent of Oregonians have already received at least one COVID vaccination shot, though just a quarter of Oregonians have received the latest booster.

The COVID rate in wastewater has ticked up in recent weeks in Oregon, which Sidelinger attributed to a new variant of the virus, though hospitalizations have remained steady. Sidelinger said that the agency is tracking a recent small increase in flu cases due to Influenza B with the season’s Influenza A outbreak having subsided. The RSV surge, which predominantly impacted children, has ended for the season.

Sidelinger also provided an update on the state of the Mpox—formerly known as monkeypox—outbreak in Oregon, saying that the state is seeing between zero and two new cases per month and encouraging people who may be at risk to get vaccinated. Oregon has had a total of 270 cases since the outbreak began last June.

“We’re seeing decreases in respiratory disease, hospitalizations, and transmission across the community,” Sidelinger said. “Our Mpox cases are very low. And this is due to the steps people have taken.”