It’s been more than 50 years since hundreds of Black families were forcibly evicted from their North Portland homes to make space for Emanuel Hospital, now Legacy Emanuel Medical Center, under the guise of “urban renewal.” Now, those Portlanders and their descendants are seeking restitution from the city for undermining their families’ chance at creating generational wealth and social stability due to the color of their skin.

On Thursday, 27 Black Portlanders and a community organization filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against the city and Legacy Emanuel for “using undue influence and intimidation to remove plaintiffs from their family homes based on their race” in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s.

“Defendants intended to deprive plaintiffs of equal protection of the law, targeting a majority-Black neighborhood for removal without due process or just compensation,” reads the lawsuit.

The 54-page complaint details decades of intent from both the city’s urban development bureau Prosper Portland and Legacy Emanuel to remove Black homeowners and business owners from the North Portland neighborhood once called Albina.

It explains the years of redlining by banks and real estate moguls that prevented Black Portlanders from buying property in most Portland neighborhoods—except for Albina. These policies, coupled with racist zoning codes, turned Albina into a thriving hub for Portland’s Black community by the 1940s. Beginning in the 1950s, however, Prosper Portland relied on the city’s eminent domain abilities to raze hundreds of homes in the Albina neighborhood to build Interstate 5 and to construct Memorial Coliseum.

Then, the city turned to the US Housing Act of 1957, which offered cities federal urban renewal loans and grants to redevelop “blighted” neighborhoods. In the early 1960s, the city met with Legacy Emanuel to discuss using urban renewal grants to help the hospital expand into its surrounding neighborhood. By the end of the decade, the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) approved the joint grant application, agreeing that the city’s only majority-Black neighborhood was blighted. Despite community pushback, Prosper Portland successfully displaced nearly 200 households and razed the empty buildings. “Of the 171 reported displaced households, 74 percent were Black, many of whom had owned their homes free and clear,” the lawsuit explains.

The community advocacy work did lead to Prosper Portland agreeing to develop between 180 to 300 units of federally assisted low-income housing to replace the demolished homes. Plaintiffs in the lawsuit contend that adequate replacement homes were never offered to their families. More recently, the city has instead offered programs to help some former residents purchase condos in the area and invested in affordable apartment complexes in the neighborhood, which plaintiffs deem insufficient. Meanwhile, the city continues to rely on urban renewal grants to make plans to develop housing on a piece of remaining property (called the “Hill Block”) that Legacy Emanuel left undeveloped.

“Portland, the City, and Emanuel have been celebrating the [Hill Block] project as ‘a great solution to address some long-standing issues’ and ‘righting a historical wrong’,” the lawsuit reads. “Yet none of them has in any way provided restitution to the direct victims of the Emanuel displacement.”

The 27 plaintiffs represented in Thursday’s lawsuit are both former residents of pre-1970 Albina and descendants of former homeowners whose properties were taken by the city. Many of the plaintiffs were children when they were forcibly removed from their families’ homes.

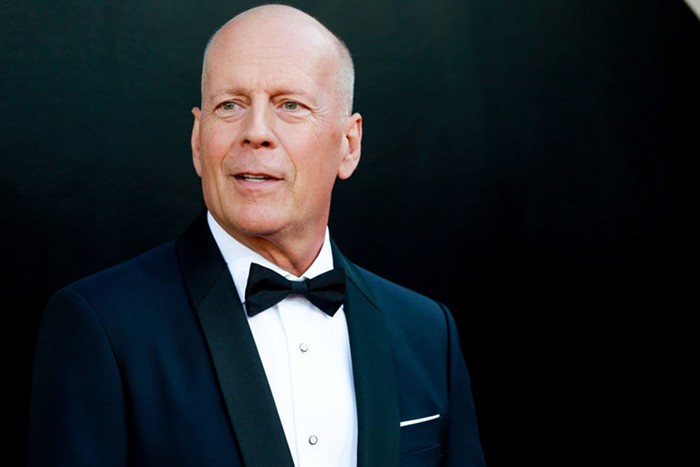

Marilyn Hasan was ten years old when representatives from Legacy Emanuel gave her family 60 days to leave their N Monroe home. The order forced her family to relocate into Irvington, a predominantly white neighborhood to the east. Hasan said her new white neighbors banned their children from playing with her.

“The move forced their family of six out of the familiar home and community where they had had everything that they needed,” the lawsuit reads. “Instead, the family had to relocate to an unwelcoming white neighborhood.”

Several of the plaintiffs mention how their families spoke about their homes as a family heirloom that would be passed down for generations.

“For [plaintiff Juanita Biggs], homeownership involved sharing family traditions, establishing roots, and providing a place for generations to carry on their Creole traditions,” that lawsuit reads. “The safety and security that Mrs. Biggs felt growing up in a nurturing Black neighborhood is incomparable. When the demolitions happened, she felt the deep disconnection of family and the loss of a lifestyle that she had known.”

Plaintiffs also point to the home improvements their families made to their properties, contradicting the city’s narrative that the area was “blighted.”

“The only ‘blight’ that [plaintiff Bobby Fouther] recalls in Central Albina occurred after Emanuel started demolishing houses,” the complaint reads.

This is underscored by attorneys later in the court filing.

"The generational loss and trauma that defendants wrought on plaintiffs were not the consequence of any actual blight, but of pure racism," it reads.

The plaintiffs are joined in the case by a community group called Emanuel Displaced Persons Association 2 (EDPA2), a group which is made up of several of the individual plaintiffs. The group is named after a 1970s Portland organization with the same acronym and mission—to fight for the families displaced by the city and hospital’s urban renewal plan. EDPA2 partnered with Portland State University to produce a study in January that quantified the financial and emotional harm done to the Black community by Legacy Emanuel and Prosper Portland. The report estimated that displaced Albina families are owed at least $89 million in property wealth appreciation.

The plaintiffs are represented by a trio of civil rights legal teams: Albies, Stark & Guerriero, Oregon Law Center, and Legal Aid Services of Oregon. The federal lawsuit accused both the city and hospital of violating their plaintiff’s civil rights, along with creating a public nuisance and being unjustly enriched by the plan.

According to the lawsuit, attorneys first notified the city about this pending complaint in September. Yet, in the time since, the city has allegedly offered “no substantive response” or effort to reach a settlement.

The city attorney's office has not yet responded to the Mercury's request for comment.

Plaintiffs want the lawsuit to be resolved in a federal trial, where a jury would be responsible for determining restitution, be it financial or otherwise.

"My great grandma owned a boarding home that helped the Black community. I'm devastated that her work didn't get passed down,” said LaKeesha Dumas, a plaintiff, in a press release issued by the legal team Thursday morning.

“There was a racist conspiracy to violate our civil rights. It's my turn to get in the fight and advocate for our family.”